Perched on the edge of insular Europe, the musical mecca of Clare covers almost 1,400 square miles of windswept mountain, blanket bogland, and limestone desert on the west coast of Ireland. Bartered historically between the western province of Connacht and the southern province of Munster, Clare sits between the barren wilderness of Connemara and the rich farm lands of Limerick and Tipperary. Throughout prolonged cycles of geological time, climate and glaciation conspired to surround the region on three sides by water and virtually isolate it from its neighbours. To the north and west, it is bordered by Galway Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. To the south and east it is hemmed in by the Shannon estuary and Lough Derg, while to the north and northwest it is cut off by the uplands of Sliabh Aughty and the lunar landscape of the Burren.

Human history in Clare began around 4000 BC, when the first Neolithic farmers arrived in the Burren karst. Speckled with over seven thousand archaeological sites — among them Bronze Age tombs, Iron Age forts, and Early Christian churches — Clare has been a research cornucopia for legions of archaeologists and natural historians since the close of the nineteenth century. The area was also layered with Viking, Norman, Elizabethan, and Cromwellian settlements, all of which left lasting imprints on the topography of the county. Few periods in Clare history, however, can compare with the social and psychological trauma of the Great Famine of the mid-nineteenth century. Sparked by an incurable potato blight, it ripped through the over-populated rural communities of the south, west, and northwest of Ireland and deprived millions of their food staple for five successive years from 1845 to 1850. By the time it was over, one million people had died of starvation, while another million had left the country in emigrant ships. Clare was in the front line of this Armageddon, which was to change forever the cultural topography of the region.

The Great Famine rocked Clare society to its foundations. In 1841, almost 25,000 Clare families lived in one-room mud cabins with inadequate ventilation and scant protection from the elements. This accounted for sixty percent of all registered houses in Clare. These homes were to become the primary victims of the famine tragedy, as hunger, disease, and emigration coincided to rid the area of entire communities. In the grim decade 1841-1851, the population of Clare fell by twenty-five percent. In all, about thirteen thousand Clare homes became uninhabited during the famine decade. 1 The anguish of Clare’s famine victims is graphically described in a plea sent on their behalf to the assistant secretary to the Treasury, Charles Trevelyan, and the Board of Works in Dublin by a Captain Wynne in December 1846:

Although a man not easily moved, I confess myself unmanned by the intensity and extent of the suffering I witnessed more especially among the women and little children, crowds of whom were to be seen scattered over the turnip fields like a flock of banished crows, devouring the raw turnips, mothers half-naked, shivering in the snow and sleet, muttering exclamations of despair, while their children were screaming with hunger. 2

Despite the feeble efforts of relief committees, public work schemes, soup kitchens, and assisted emigration to America (which was minimal from Clare), the burden on the lower social classes continued to worsen into the early 1850s. With the economic pyramid crumbling beneath them, Clare landlords responded with callous severity. They set the pace for mass evictions in Ireland. With 3.2 percent of the Irish population, the county experienced 8.3 percent of all permanent evictions recorded by the Royal Irish Constabulary in the years 1849-1854.3 Increased costs and declining rents drove some landlords, like the Marquis of Thomond, who owned 40,000 acres, from mortgage to mortgage and eventual bankruptcy. Others, like the Machiavellian Vandaleurs in Kilrush (about whose purchases of Wheatstone concertinas, see below), opted for mass evictions and house leveling in an attempt to rid the countryside of inefficient rundale farms.4 Chronicled in horrific detail by the Illustrated London News, many of these clearances were conducted with untold brutality by land agents like Marcus Keane on the Iorrus peninsula. Keane, who exercised control over 60,000 acres, leveled as many as five hundred homes on behalf of his ascendancy clientele.5 From November 1847 to July 1850, more than 14,000 people (2,700 families) were evicted in the Kilrush Union alone, an exodus unparalleled in any other part of Ireland. Evicted tenants had few options, none of which was appealing. The prospect of being admitted to the workhouse was tantamount to a slow death, with cholera, malnutrition, and family breakup included as part of the destitute package. Many chose instead to brave the elements — and defy the law — by making temporary shelters in scailps (bog holes), behind stone walls, or in ditches, using the remnants of their broken homes as makeshift shelters.

The Grim Requiem of the Music Maker

While Crown clerks compiled sterile statistics on the famine catastrophe, and journalists tugged at the heartstrings of the literate public, the folk poet, the singer, and the music maker indexed the cultural cleansing of the Great Famine from the humanistic perspective of the famine victims themselves. Reflecting in lucid detail upon the inner world of the Irish-speaking clachán, famine songs, piping airs, and musical-place lore chronicled the demise of community life, work rituals, calendar customs, and folk beliefs. These anonymous tunes also mirrored the ultimate demise of their own keepers, who had given them a voice in the living traditions of pre-famine Ireland.

In Clare, where tradition-bearers and listeners, repertoires and musical territories were ravaged irrevocably by starvation and diaspora, folkloric evidence cites musicians ending their days in the workhouse, instrument makers going to ruin, and pipers following their audiences into exile in the New World. Contemporary antiquarians like George Petrie and Eugene O’Curry, who collected music and songs from clachán-based informants in West Clare prior to the famine, reflect sadly on the ‘silence’ which had been inflicted on the ‘land of song’.6 Their pessimism was an epitaph for the old world of the swaree and the dancing master, the townland and the fairy path, which had now ceded its place to a more conservative and materialistic milieu.7

While they cannot be regarded in the same light as orthodox eyewitnesses, traditional musicians did observe the famine droch-shaol (bad life) at close quarters. Their grim requiem contains cogent observations of its impact in rural communities.8 The small fragments of Clare songs which survived in Irish, like that recorded from Síle Ní Néill in Coolmeen, focused on the interwoven themes of mortality, destitution, and exile from the ‘insider’ perspective of the victims and their immediate kin. The following verse, recorded from Seán Mac Mathúna, who was born in Luach near Doolin in 1876, is a poignant case in point:

Is dána an rud domhsa a bheith ag súil le comhra

Is maith an rud domhsa má d’fhuighinn braillín

Is a Rí na Glóire tabhair fuscailt domhsa

Go dté mé im´chónaí san gcill úd thíos.9It is a bad thing for me to expect a coffin

It will be a good thing for me to get a sheet

And God of Glory, grant me solace

Until I go to dwell in that graveyard below.

(My translation)

Despite the cultural cleansing of the Great Famine, almost a half-century would pass before the indigenous piping dialects of Clare would finally expire. In the years after 1850, a few itinerant pipers managed to eke out a livelihood in the small towns and villages in the west of the county. For example, Paddy O’Neill and John Quinlan worked as pipers on riverboats plying the Shannon between Limerick and Kilrush. Quinlan, who was commonly known as ‘Jack the Piper’, also played for holiday makers in Lahinch and Lisdoonvarna.10 In the Sliabh Aughty uplands of East Clare, the last remnants of local piping died with Mick Gill and Michael Burke before the end of the century. One of the last pipers of note to visit the area was Loughrea man Pat Twohill, who, along with his brother John, had worked as a professional piper in England during the 1860s. Twohill’s younger brother James was father of the celebrated American piper Patsy Touhey, who emigrated from Loughrea, Co. Galway, with his parents in 1869.

Fleeing the depression of the post-famine era, several Clare pipers followed their audiences into exile in the New World. Corofin-born Patrick Galvin left Clare for New Zealand in the late 1850s. Dubbed ‘The New Zealand Piper’ by the collector Francis O’Neill, it would be forty years before Galvin would return again to his native place. His contemporary, Johnny Patterson, was the most flamboyant of Clare’s emigrant pipers. In his celebrated ditty ‘The Stone Outside John Murphy’s Door’, Patterson immortalized his impoverished childhood in the hovels of Old Mill Street in Ennis. Having survived the worst effects of the famine, Patterson joined the British Army, where he received piccolo and drum lessons in the army band. At the end of five years of service, he bought his way out of the army and joined Swallow’s Circus. For the next forty years, Patterson toured Ireland, England, and the United States with a variety of circus companies. Dubbed the ‘Rambler from Clare’, Patterson featured piping in many of his shows, especially in the United States, where he was billed as a ‘Famous Irish clown and piper’. His songs include such Irish-American standards as Good Bye Johnny Dear, The Hat My Father Wore, The Garden Where the Praties Grow, and The Roving Irish Boy, and thrived on emigrant sentimentality.11

Pipers were not the only music makers to take their leave from Clare. Fiddlers and flute players were also conspicuous among Clare émigrés in North America. Fiddler Paddy Poole from Tulla spent many years in the United States in the late nineteenth century. He began teaching fiddle in East Clare after he returned home in the 1920s. Poole spent some time in Chicago, where he played with the vaudevillian piper Patsy Touhey. Flute player Patrick O’Mahony from West Clare also found his way to Chicago in the early 1880s. There he joined the police force and contributed numerous Clare dance tunes to the published collections of Francis O’Neill.12

It was into this milieu of cultural upheaval and musical change that the Anglo-German concertina arrived in Clare during the middle decades of the nineteenth century. It would eventually replace the uilleann pipes (whose exponents were ravaged by famine and exile) as a popular vernacular instrument. While its presence was especially felt in fishing, piloting, and trading communities along the lower Shannon estuary — one of the busiest riverine networks in Ireland during the nineteenth century — its espousal by women music makers would become its most enduring sociological feature at a time when women in Irish society were, for the most part, subservient players in a ubiquitous patriarchal milieu.13

Newfound Wealth, River Pilots, and Women’s Concertinas

Women born into rural communities in post-famine Clare grew up in a spartan, materialistic world. As non-inhering dependents in a patriarchal culture, women shared a common fate with servant boys, farm laborers, and disinherited males on the family farm. As the ‘disinherited sex’, they were deprived of the independent income, however meager, they enjoyed from domestic industry prior to the famine.14 With marriage becoming an economic union more often than an amorous one, wives became increasingly subservient to their domestic masters, their husbands. Similarly, unmarried sisters were governed by the whims of their fathers and brothers. For women lacking the luxury of a dowry or a farm to boost their economic status, their only escape was to emigrate, or else to find work as servant girls or shop attendants in a nearby town.

As the landless laborer and the clachán disappeared from the Clare countryside, the average size of farms got bigger. In the resulting economic transformation, it became increasingly difficult to marry above or below one’s ‘station’. As strong farmers refused to marry their daughters to laborers, the social choice for prospectors in the marriage market narrowed considerably.15 The age of marriage also changed. Sons waiting to inherit the family farm tended to be more patient than daughters waiting for a husband. Hence, husbands tended to be older than their wives. The widening age gap between spouses created a high proportion of widows at the other end of the life cycle. Wives and widows, many of them victims of loveless matches engineered by their fathers or local match makers, often projected their hunger for affection onto their eldest sons, and dreaded the rivalry of a daughter-in-law, who would ultimately compete with her for her son’s loyalty.

By the 1890s, however, the climate of frugality, which had marked the previous decades, began to wane, and the quality of women’s lives improved. Successive Land Acts and the deft attempts of Tory governments to ‘kill Home Rule with kindness’ led to an overall improvement in social and economic life in the Irish countryside. Inspired by similar developments in Denmark, Sir Horace Plunket’s cooperative movement helped to improve Irish agriculture, especially dairy farming. Plunket founded the first of his dairies, or ‘creameries’ as they are called in rural Ireland, in 1889 to upgrade the quality of Irish butter and cheese.16 Within a decade, creameries became common landmarks in most rural parishes. Following the brief failure of the potato crop in 1890, the future Prime Minister Arthur Balfour introduced a number of light railway schemes. In 1891, the Congested Districts Board was established to amalgamate farms and improve living conditions in impoverished western areas. Similarly, political devolution took an unprecedented step forward in 1898, when the Local Government Act created urban and county councils all over Ireland.

Clare was among the beneficiaries of these economic changes. The West Clare Railway had been incorporated in 1883. Within a decade, its South Clare line, linking Kilrush, Kilkee, and Miltown Malbay, was completed. As well as improving travel within the county, the railway introduced a whole range of consumer goods and services, which were once beyond the reach of its patrons. The combined effects of increased communication, the co-op movement, and the Congested Districts Board helped to generate new independent income for women in rural Clare. By the end of the century, many were taking advantage of the buoyant economic climate to sell eggs and butter in local country shops or nearby village markets. Others boarded the ‘West Clare’ to transport animals and garden produce to market towns along the railway line. This new domestic income allowed women to buy a range of goods, including cheap concertinas, which became ubiquitous in rural communities by the early 1900s. Their intriguing espousal of this hexagonal squeezebox would have far-reaching musical and social consequences.

Influenced by the Chinese shêng, and perhaps the Laotian khaen (ancient free-reed instruments brought to Europe by French Jesuit missionaries in the eighteenth century), the concertina had come to fruition during the Romantic period. The English concertina was patented by Sir Charles Wheatstone in 1829. Popular in music salons and parlors from Victorian England to Tsarist Russia, Wheatstone’s expensive chromatic instrument remained a ‘high art’ curiosity for most of the nineteenth century, though by the 1880s, it had found its way down into the ranks of working class musicians in industrial England, as well as into traditional music communities in rural Lancashire, the Cotswolds, and Central Midlands. It would be another half century, however, before a single-action Anglo version of Wheatstone’s concertina would become popular in the west of Ireland.17

Although the Dublin concertina manufacturer Joseph Scates advertised his instruments in the popular Freeman’s Journal as early as 1852, there is no evidence to suggest that his concertinas enjoyed widespread popularity among music communities in contemporary Clare.18 Moreover, though the names of such aristocratic Clare families as the Vandeleurs, Tolers, and Abingers appear in the sales ledgers of the London Wheatstone company during the 1840s and 1850s,19 oral history contends that the first concertinas to arrive en masse into Clare were German-made imports. Fragile, cheap, and short-lived, these ‘consumer’ instruments were probably adapted from Carl Uhlig’s diatonic konzertina made in Chemnitz, Germany, in the 1830s, and popularized by Manen’s twenty-key concertinas that reached the English marketplace in 1847. These cheap instruments enjoyed widespread popularity among sailors on long sea voyages and were stocked by maritime chandlers as part of their stoc

As well as servicing vessels arriving from foreign ports, islanders and river men along the Shannon had extensive ocean-going experience themselves. Ships owned by Limerick merchants enlisted crews from communities on both sides of the river in Clare, Limerick, and Kerry. Merchant seamen from Scattery Island, on the mouth of the estuary, had a long history of maritime travel. In 1903, for example, the three-master sailing ship the Salterbeck, owned by Captain James Murray of Kilrush, was transporting kelp and flagstones from Cappagh across the Atlantic to St. John’s, Newfoundland. Its crew ‘to a man’ was from Scattery. According to folklore collected on Scattery Island by Seán Mac Craith in 1954, the Salterbeck made the round trip across the Atlantic in the spring of 1903 in a record-breaking ‘eight weeks and five days’. 21 Up until the 1950s, social life on Scattery showed all the signs of maritime wealth. Book collections, eight-day clocks, and wireless sets were standard fittings in many island homes. In the 1920s, the islanders were among the first people in Clare to own Victrola-type gramophones and 78 rpm recordings of Irish traditional music. These were brought back to Scattery from America by merchant seamen from the island. It is likely that German concertinas reached West Clare through these same maritime channels.

By 1900, the concertina had replaced the uilleann pipes as a household instrument in rural Clare. Women earning surplus income from egg and butter sales, as well as other domestic industries, were among its chief patrons. In the vernacular of West Clare, the instrument was referred to as a bean cháirdín (female accordion), such was its popularity among female players. By 1910, concertinas were being stocked by hardware stores and bicycle shops in Ennis, Kilrush, Kildysart, and Ennistymon. They were usually bought on market days after poultry or dairy produce had been exchanged for money. Women, whose cottage earnings were consistent from year to year, could afford to upgrade to a new concertina, for the princely sum of half-a-crown, every few years.

The concertina was given pride of place in the country house kitchens of West Clare. Like tea, tobacco, and other domestic commodities, which were stored in a dry place, a special clúid, or alcove, was constructed for the concertina in the inner wall of the hearth, close to the open fire. Although many houses had resident concertina players who knew enough tunes to play for a polka set, some non-musical households also purchased concertinas, which they kept on hand in the alcove for a local concertina player to ‘come on cuaird to the house’ (literally ‘come on a visit to the house’).22 Unlike the daughters of strong farmers who learned to read piano scores and classical arias in bourgeois convent schools, young women who bought concertinas ‘out of their egg money’ learned their music informally in a kitchen setting. In this largely egalitarian environment, there was no obligation to learn an extensive repertoire, or to rise to certain predetermined standards of musical excellence. Many country house débutantes used a numbering system to learn tunes, while others relied on a more direct process of aural transmission. The primary objective for most young concertina players was to perfect local jig, reel, and polka rhythms, and to learn enough dance tunes to play for the Plain Set dance. In this self-contained rural milieu, proactive sharing of music and dance was considered far more important than the private appreciation of ‘high-art’ music from a distant urban periphery, which was then becoming the norm in many bourgeois families in the west of Ireland.

For most of the next century, concertina music would dovetail with the indigenous set dancing dialects of rural Clare and find its main patrons in rural communities in the west and east of the county. When Anglo-German concertinas made by Jeffries, Wheatstone, and Lachenal flooded the antique markets in Petticoat Lane after World War II, Clare musicians working in London became a key source for delivering concertinas to their neighbors back home. Henceforth, emigrant parcels, music shops, and hardware stores became the chief suppliers of new instruments, which were really ‘cast off’ instruments from the upper echelons of British society.

Clare Concertina Dialects and Players

In the period 1890-1970, concertina playing in Clare took place primarily in mountain communities (above the 200-foot contour) to the north and east of the county, and in the blanket boglands of West Clare.

Topographical examination of these concertina territories reveals four musical ‘dialects’ which were formed by clachán-type community clusters during the post-famine era, and which dovetailed with the indigenous set dancing dialects of rural Clare.23 The concertina dialect of south West Clare was highly rhythmical, melodically simple, and characterized by single-row fingering techniques on Anglo-German instruments. The Plain Set danced to polkas predominated in the region prior to the diffusion of the ubiquitous Caledonian Set in the 1920s and 1930s. Because of the influx of traveling teachers like fiddler George Whelan who crossed the Shannon from Kerry, the music of the area was linked umbilically with the polka and slide repertoires of Kerry and West Limerick. Hence, older concertina players like Charlie Simmons, Solus Lillis, Elizabeth Crotty, Matty Hanrahan, Frank Griffin, and Marty Purtill played a variety of archaic polkas and single reels. The Caledonian Set, however, facilitated more complex double reels, which were favored by players like Tom Carey, Sonny Murray, Tommy McCarthy, Bernard O’Sullivan, and Tommy McMahon.

The concertina dialect of mid West Clare was shaped explicitly by the rhythmic complexities of Caledonian set dancing, as well as the by American 78 rpm recordings of Co. Westmeath exile William J. Mullaly, which were prefaced by the dispersal of gramophones in the area during the 1920s. Dominated by the brean tír uplands of Mount Callan, this area extends from the Fergus Valley in the east, to Quilty on the Atlantic seaboard. Home to celebrated concertina masters such as Noel Hill, Edel Fox, Miriam Collins, Michael Sexton, and Gerard Haugh, as well as the late Tony Crehan and Gerdie Commane (see Example 1 in the Appendix for his version of ‘The Kilnamona Barndance’), the region still houses the steps and dance figures of Pat Barron, the last of the traveling dancing masters to teach in West Clare in the 1930s. Complex cross-row fingering, intensive melodic ornamentation, and a formidable repertoire of dance tunes mark the indigenous concertina style of this region.

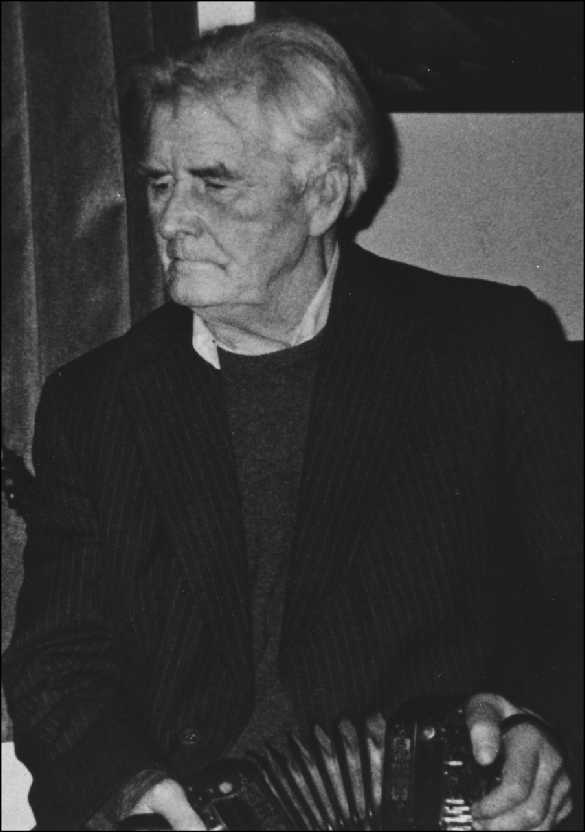

The most outstanding concertina master in mid West Clare in recent times was Paddy Murphy from Fiach Roe, a rural community on the brow of Mount Callan (see Figure 1) . Influenced by the American concertina recordings of William J. Mullaly in the late 1920s,24 Paddy pioneered a unique system of cross-row fingering which facilitated the use of alternative scales for tunes in unfamiliar keys.25 The first Irish-born concertina player to broadcast on Irish radio, Paddy Murphy was also a competitive pioneer of the instrument. His victory at the All-Ireland Fleadh Cheoil (National Music Competition) in Cavan in 1954 marked the first-ever appearance of the concertina in an Irish national music competition. This forum has since attracted thousands of concertina players from all over Ireland, Britain, and North America. Much of Murphy’s vast repertoire (see Example 2 in the Appendix for his version of ‘The Moving Cloud’) was learned aurally from the fiddling of the local postman, Hughdie Doohan, who had a rare ability to read music from O’Neill’s Music of Ireland, which was published in Chicago in 1903 and enjoyed biblical status among Irish music communities by the 1920s and 1930s. Doohan, who was a key member of the local Fiach Roe Céilí Band, made well sure that his cohorts (whose skills of musical acquisition were primarily aural) would not want for access to the largest data bank of traditional Irish dance melodies in the world at the time.

Fig.1. Clare concertina master Paddy Murphy, 1990 (© Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin,1990)

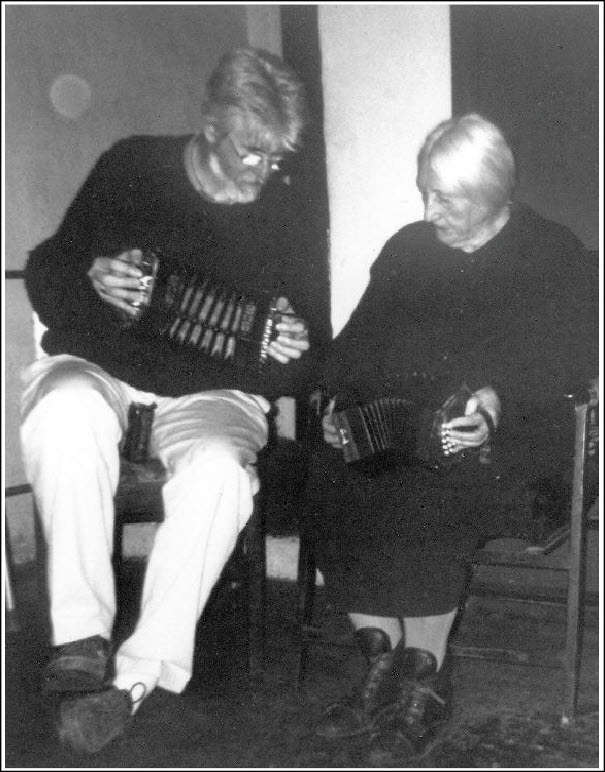

North Clare consists of three concertina communities situated along the perimeter of the Burren karst, all of which shared a common musical dialect. Two of these, Doolin and Bellharbour, were coastal, while the third was located in Kilfenora and Kilnaboy in the south Burren. With the curious exception of Pakie Russell (whose innovative style also explored cross-row fingering), most of the older players in North Clare favored melodically simple music and single-row fingering techniques, accentuating the inside or G row of the Anglo-German concertina. The overriding characteristic of this dialect was its emphasis on rhythm and ‘lift’ for set dancers. This ‘lift’ was endemic in the music of Peadaí Pheaitín Ó Flannagáin, James Droney, Brody Kierse, Biddy McGrath, and Michilín Connollan. It is still conspicuous today in the concertina playing of Chris, Ann, and Francis Droney (see Figure 2), Máirtín Fahy and Mick Carrucan, all of whom are extolled by North Clare set dancers.

k-in-trade merchandise. German concertinas arrived in Clare through a variety of sources, some direct and conspicuous, others oblique and vicarious. Its initial courier was most likely river traffic plying the Shannon between Loop Head and Limerick city, the last port of call for tall ships before crossing the North Atlantic.

Superceded to some degree by the West Clare Railway after 1892, the Shannon had been one of the busiest waterways in insular Europe throughout the nineteenth century.20 Apart from foreign cargo, the river had a thriving local trade. Steam boats carried stout, butter, and coal between Limerick and Kilrush, while turf boats brought turf up the river from as far west as Kilbaha. With its bustling ports, brisk shipping trade, and onerous navigational challenges, the river offered employment to shipwrights, dockers, coopers, lighthouse keepers, and fishermen who lived along its banks. The lives and activities of these riverine communities have been recorded extensively in the traditional songs and folklore of West Clare. Maritime superstitions, ghost ships, sea monsters, and mermaid legends are all part of the rich repository of Clare sea lore.

Fig. 2. Three generations of the Droney family from Bellharbour, northwest Clare,1969: Ann, James, and Chris. Chris Droney continues to enjoy a formidable reputation both in Ireland and among Irish concertina players in Europe and North America (© Chris Droney. Courtesy of the Droney family, 1988).

Concertina music in East Clare was concentrated along the Clare-Galway border in Sliabh Aughty, in the drumlin belt of Clooney and Feakle, and above the fertile lowlands of the Shannon, in Cratloe and Kilfentenan. German-made concertinas predominated in the region during the early 1900s, most of which were owned by women who seldom played beyond the confines of their own kitchens. The archaic repertoire and ethereal settings of Sliabh Aughty found a resolute custodian in concertina master John Naughton of Kilclaren. Many of his settings were shared by Connie Hogan from Woodford in East Galway, where dance music was dialectically linked to the repertoires played in neighboring communities in East Clare. The house music of the drumlin belt to the south was typified by the concertina playing of Mikey Donoghue, Bridget Dinan, and Margaret Dooley, the latter two continuing to play well after their one-hundredth birthdays. The concertina music of Cratloe and Kilfentenan survived until recent times in the playing of Paddy Shaughnessy and John O’Gorman. Reminiscent of an older world of cross-road dancing and rural ‘cuairding’, their traditional milieu was purged by the suburban sprawl of cosmopolitan Limerick and, ironically, ignored by the revival of traditional music in nearby towns and villages during the 1970s. The most prominent exponent of East Clare concertina music today is Mary McNamara, who has sustained a vibrant corpus of dance tunes from such masters as John Naughton and Mikey Donoghue. (See Figure 3 for a topographical map of Clare concertina music, 1880-1980.)

Fig. 3. Topography of Clare Concertina Music, 1880-1980 (©Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin)

Clare Concertina Music Today

Concertina music in Clare has experienced a phenomenal upsurge since the 1980s, not least as a result of schools like Scoil Samhraidh Willie Clancy and Éigse Mrs. Crotty, which have created a forum for master performers and students. While this upsurge has attracted huge numbers of students to the instrument, it has failed to stem Clare Concertina Music Today Concertina music in Clare has experienced a phenomenal since the 1980s, not least as a result of schools like Scoil Samhraidh Clancy and Éigse Mrs. Crotty, which have created a forum performers and students. While this upsurge has attracted huge of students to the instrument, it has failed to stem the inevitable decline of regional concertina dialects in Clare. Conversely, recent developments in competitive performance and commercial recording have spurred the growth of a ‘modernist’ generic style and a meticulous imitation of professional performers, a practice that is not without precedent in Irish music history. While this homogenization has raised the level of technical accomplishment in Clare concertina playing, it has also led to the emergence of prodigiously ornamented tune settings and the introduction of non-indigenous repertoires. Similarly, it has led to an increased separation between ‘performance’ music and ‘dance’ music. Older players, whose sense of rhythm was implicitly linked to set dancing, often feel isolated by younger players who have eschewed the traditional dance milieu for the concert stage and television studio. Among the minority of younger players who continue to sustain the older dialects of Clare are Jacqui McCarthy, Florence Fahy, Breeda Green, Louise Pyne, and Francis Droney.

Foremost among an innovative corps of ‘modernist’ performers are Edel Fox, Pádraig Rynne, Hugh Healy, John McMahon, and Noel Hill, whose technical genius has propelled the concertina music of Clare well beyond the perimeters of its former communal dialects and whose teaching has helped to create a vast transnational network of Anglo-German concertina enthusiasts who are truly devoted to the concertina music of their Clare mentors. Like their predecessors in the early 1900s, women continue to dominate Clare concertina music. Among its celebrated female exponents are Yvonne and Lourda Griffin, Bríd and Ruth Meaney, Dympna Sullivan, Lorraine O’Brien, and Edel Fox, a recent recipient of the ‘Young Traditional Musician of the Year’ award from Irish national television. It is noteworthy

that longevity is common among female concertina players in Clare. Both Margaret Dooley and Bridget Dinan in East Clare lived well over one hundred years. Similarly, Susan Whelan of Islebrack celebrated her centenary in 1991 by playing a few tunes on her new Czechoslovakian concertina. The oldest musician in Clare until her death in December 2000 at the age of one hundred and four was concertina player Molly Carthy from Lisroe (see Figure 4). Having played music in three centuries, Molly entertained her family nightly (until a week before her death) by playing dance tunes on a teetering Bastari concertina made in Italy. Such centennial temerity bodes well for the future of concertina music in Clare and its renowned female guardians, especially now at the dawn of another new century and another brave new world of Irish concertina music.

Fig. 4. The author with 101-year-old concertina player Molly Carthy, Clare, 1997 (© Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin, 1997).

NOTES

1. Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh, ‘Aspects of the Economy and Society in Nineteenth Century Clare’, Dal gCais: Journal of Clare, 5 (1979), 110-14.![]()

2. Brian Dinan, Clare and Its People: A Concise History (Cork: Mercier Press, 1987), 96.![]()

3. James S. Donnelly, Jr., ‘The Kilrush Clearances during the Great Famine’, paper presented at the annual conference of the American Conference for Irish Studies, Fort Lauderdale, Florida (April, 1998).![]()

4. Clacháns (small rural villages or hamlets) associated with open-field rundale farms (using an infield/outfield system of crop rotation) were common in most parts of rural Ireland in the century before the outbreak of the Great Famine; see E. Estyn Evans, The Personality of Ireland: Habitat, Heritage and History (Belfast: Blackstaff Press, 1981), 55.![]()

6. George Petrie, The Complete Collection of Irish Music, ed. Charles Villiers Stanford (London: Boosey, 1902-1905), vol. 1, xii.![]()

7. The term swaree from the French soirée is a remnant of the Gallicized vocabulary of the pre-famine dancing masters.![]()

8.The famine years were referred to as ‘an droch-shaol’ (‘the bad life’) in Irish speaking communities. The use of the popular term ‘gorta’ (‘famine’) was a much later development.![]()

9. Cited in Cathal Póirtéir, Glórtha ón Ghorta: Bealoideas na Gaeilge agus an Gorta Mór (Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim, 1996), 286.![]()

10. Francis O’Neill, Irish Minstrels and Musicians (Chicago: Reegan, 1913), 230-31, 342-43. W.R. le Fanu gives a colorful description of meeting Paddy O’Neill on board the ‘Garry Owen’ (a boat plying the Shannon between Limerick and Kilrush) in his Seventy Years of Irish Life (New York: Arnold, 1898); cited in O’Neill, Irish Minstrels and Musicians, 230.![]()

11. Harry Bradshaw, ‘Johnny Patterson: The Rambler from Clare’, Dal gCais: Journal of Clare, 6 (1982), 73-80.![]()

12. O’Neill, Irish Minstrels and Musicians, 18-19.![]()

13. See Margaret MacCurtain and Donncha Ó Corráin, eds., Women in Irish Society: The Historical Dimension (Dublin: Arlen House; The Women’s Press, 1978).![]()

14. J.J. Lee, ‘Continuity and Change in Ireland 1945-1970’, in J.J. Lee, ed., Ireland 1945-1970 (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1979), 166-77.![]()

15. Lee, The Modernization of Irish Society 1848-1918 (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1973), 4.![]()

16. F.S.L. Lyons, Culture and Anarchy in Ireland 1890-1939 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979), 53.![]()

17. Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin, ‘The Concertina in the Traditional Music of Clare’, Ph.D. dissertation, Queen’s University, Belfast (1990), 47-72; see also Allan W. Atlas, The Wheatstone English Concertina in Victorian England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996), and, on the matter of the patent, Atlas, ‘Historical Document: George Grove’s Article on the “Concertina” in the First Edition of A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (1878)’, Papers of the International Concertina Association, 2 (2005), 61.![]()

18. See Fintan Vallely, ed., The Companion to Irish Traditional Music (Cork: Cork University Press, 1999). 83. Scates, who imported pianos, harmoniums, and Wheatstone concertinas, traded at 26 College Green, Dublin, a very fashionable Dublin location at the time.![]()

19. I draw here on Allan Atlas, ‘Ladies in the Wheatstone Ledgers: The Gendered Concertina in Victorian England, 1835-1870’, forthcoming in the Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle, 39 (2006). Briefly the following members of these families are recorded in the ledgers: Lady G[race] Vandeleur, 1 May 1855 (ledger C1049, 53) and 21 June 1855 (C1049, 58); a Lieutenant Vandeleur, 6 November 1856 (C1050, 38); Lady Elizabeth Toler, 12 March 1851 (C1047, 11); and Lord Abinger (= Robert Campbell Scarlet, 2nd Baron of Abinger and father of Lady Elizabeth Toler), 28 April 1842 (C1046, 13, and C104a, 27). The nine extant Wheatstone & Co. sales ledgers from the nineteenth century are housed in the Horniman Museum, London, Wayne Archive; they are online at http://horniman.info. My thanks to Allan Atlas for sharing this information with me prior to its publication.![]()

20. Seán Spellissy, ‘The Fergus Estuary: Reclamation and the Life of a River Pilot’, Dal gCais: Journal of Clare, 8 (1986), 31-35. See also Kevin Danaher, In Ireland Long Ago (Cork: Mercier Press, 1962), 118.![]()

21. Bairbre Ó Floinn, ‘The Lore of the Sea in County Clare: From the Collections of the Irish Folklore Commission’, Dal gCais: Journal of Clare, 8 (1986), 107-28.![]()

22. In the ‘macaronic’ (half-Irish, half-English) linguistic milieu of late nineteenth-century Clare, Irish language terms and phrases still enjoyed currency in the vernacular speech of rural communities, an uneasy reminder of the cultural cleansing effects of the Great Irish Famine (1845-1850).![]()

23. See Ó hAllmhuráin, ‘The Concertina in the Traditional Music of Clare’, 95, 432.![]()

24. Harry Bradshaw, liner notes to the recording William Mullaly: The First Irish Concertina Player to Record (Dublin: Viva Voce 005, n.d).![]()

25. Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin ‘From Hughdie’s to the Latin Quarter’, Treoir: The Book of Traditional Music, Song and Dance, 25/2 (1993), 40-44.![]()

Select Discography

Bernard O’Sullivan and Tommy McMahon, Clare Concertinas: Bernard O’Sullivan and Tommy McMahon, Topic-Free Reed, 502 (1975).

John Kelly, John Kelly: Fiddle and Concertina Player, Topic-Free Reed, 504 (1975).

Various Clare Concertina Players, Irish Traditional Concertina Styles, Topic-Free Reed, 506 (1975).

Pakie, Micko, and Gussie Russell, The Russell Family Album, Topic, 251 (1977).

Noel Hill, Noel Hill: The Irish Concertina, Ceirníní Cladaigh, CC 21 (1988).

John McMahon featured in Fisherstreet: Out in the Night: Music from Clare Mulligan, CLUN 57 (1991).

Mary McNamara, Mary McNamara: Traditional Music from East Clare, Ceirníní Cladaigh, CC 60 (1994).

Chris Droney, Chris Droney: The Fertile Rock, Cló Iar-Chonnachta, CIC 110 (1995).

John Williams, John Williams, Green Linnet, GL 1157 (1995).

Gearóid ÓhAllmhuráin, Gearóid ÓhAllmhuráin: Traditional Music from Clare and Beyond, Celtic Crossings, CC2005 (1996/2005).

Tommy McCarthy, Tommy McCarthy: Sporting Nell: Concertina, Uilleann Pipes and Tin Whistle, Maree Music, MMC 52 (1997).

Tim Collins, Dancing on Silver: Irish Traditional Concertina Music, Cróisín Music, CM 001 (2004).

Ex. 1. Gerdie Commane’s version of The Kilnamona Barndance. The late Gerdie Commane, who died in December 2005, at the age of 88, was one of Clare’s most celebrated traditional concertina players. His recording with Inagh fiddler Joe Ryan, Two Gentlemen of Clare Music (Ennis: Clachán Music, 2002), is a landmark in archival recording (transcription © Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin, 1990).

Ex. 2. Paddy Murphy’s version of The Moving Cloud reel. Composed by Donegal fiddler Neillidh Boyle, this reel is regarded as a pièce de résistance by free-reed players in Ireland. This transcription shows Murphy’s consummate mastery of alternative scales, melodic variations, and complex ornamentation techniques (transcription © Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin, 1990).