In his contribution to the ‘Picture Gallery’ in PICA 2 (2005), Chris Algar gave a clear account of the transition that took place with respect to the concertina types used by The Salvation Army.1 Both historical circumstances and documentary evidence confirm that instruments of the Jeffries/Anglo type gave way to English and Triumph (Crane) systems during the first two decades of the twentieth century.

The five-row system adopted by the Liverpool music dealer Crane & Sons—and subsequently manufactured for them by Lachenal—was not patented by John Butterworth until 1896.2 Thus any adoption of this system, and the change of name to Triumph by The Salvation Army, had to occur after that date. As for the introduction of the English fingering system: though early paintings and engravings clearly show Jeffries/Anglo types,3 and though Salvation Army advertisements from the turn of the century still give prominence to the Anglo-German concertina, the 1904 edition of the Army’s Concertina Tutor, whilst still being primarily for the Anglo-German instrument, contained ‘a Supplementary Part. . .giving a complete course of Instruction for the English Concertina’ (see Fig. 1).4

Fig. 1. An Advertisement for the 1904 edition of the Salvation Army’s Concertina Tutor in The Salvationist, 18/Pt. 12 (June 1904), outside rear cover.

(Click to enlarge)

Thus from a starting point set early in the twentieth century, the adoption of the Crane and English systems was, as Algar points out, accomplished by the end of World War I, in a matter of less than twenty years. The evidence for this is compelling. In addition to photographs, there are numerous personal accounts. For instance, Bramwell Thornett recounts purchasing a Triumph model, with thirty-five bone keys and rosewood ends, in 1920 for a little over £5.5 He had been inspired at the time by Brigadier Archie Burgess, himself a master of the Triumph (Crane) duet.6 Although Thornett chose the same model as his teacher (Burgess), he notes that his parents ‘played a Jeffrey’s [sic] model tuned to B flat for band use in earlier days’.7 Ernest Ripley records purchasing his Triumph concertina on 2 May 1932 for £14.15, obtaining it from the ‘S.P.& S.’, the Salvationist Publishing and Supplies retail centre, as a used instrument ‘guaranteed in perfect condition’, and, by strange coincidence, ‘used by Major Burgess in Staff Band programmes as a solo instrument’.8

By the 1930s, then, the Triumph (Crane) and English systems were clearly the Army’s instruments of choice, a conclusion reinforced by the definitive tutors that they issued for those instruments at the time.9 Significantly, there is nothing for—or even a reference to—the Anglo system.

With a nostalgic look to the past, Norman Armistead would comment: ‘It seems to me that The Salvation Army ethos—musically speaking—is best represented by the humble concertina’.10 This versatile instrument—Crane and English—now came to play three roles, as concertina bands were formed in many places throughout the United Kingdom—Bristol, Plymouth, Doncaster, Harlesden and Norwich, to mention but a few. The concertina became invaluable as a solo instrument, adding worthy variation to any musical programme, and was considered by many to be indispensable as an accompaniment to voices, particularly when used in the Army’s open-air evangelical meetings. Some players became very efficient, so that Alf Lockyer was known to both lead and accompany a choir as he played directly from the four-part S-A-T-B vocal arrangement. Bramwell Thornett admits to having an instrument to his own specifications, dropping some of the duplicated keys and reeds on the left hand side and substituting bass notes, thus extending the instrument without adding to its weight.11 And if Frank Butler deprecated this practice, regretting that concertina makers were always prepared to build exceptional instruments,12 Neil Wayne takes a rather more philosophical view of such idiosyncratic systems: ‘Wheatstones would have made anything, however bizarre!’ 13

In all, the evidence for the change from the Anglo system to the Crane and English systems is undeniable. Moreover, the shift coincides precisely with what was happening among the ‘secular’ concertina prize bands of the same period. As Nigel Pickles points out, the Mexborough English Concertina Prize Band was formed in 1897 as an Anglo concertina band, but quickly changed to the more flexible English concertina prior to winning a competition at Woodkirk in 1903.14 Likewise, having excelled at the Crystal Palace competition of 1909, the members of the Heckmondwike English Concertina Premier Prize Band were pleased to pose with their instruments, their English-system layout clear for all to see.15 Finally, a 1913 photograph of the New Bedford (Massachusetts) Concertina Band shows that, while English-system instruments still formed a minority, they were taking their place among the Anglos.16

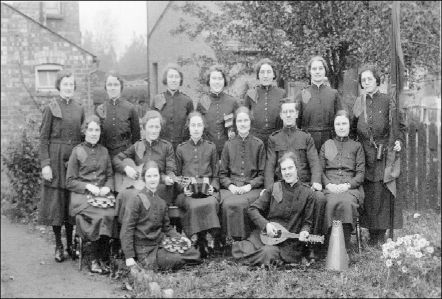

Whilst Chris Algar’s conclusions in the ‘Picture Gallery’ regarding the date of the change in instrument types are well substantiated, his juxtaposition of the two photographs is somewhat unfortunate. The Norwich Citadel photograph (page 66) is correctly referred to as their Concertina Band, but the second photograph (page 67) requires further comment. The caption to the photograph is correct, stating that the subjects are the Sergeants at the International Training College in 1931. However, the text inadvertently refers to them as ‘the Sergeants’ International Training College Band of 1931’. The photograph was taken on the entrance steps to The Salvation Army International Training College,17 opened just two years earlier, as a memorial to their founder, William Booth, for the purpose of training its officers, that is, its Ministers. The Sergeants were the ‘elite’, chosen from the Cadets of the previous session to act as junior staff over the next incoming group of Cadets. Typical of the photographs of that period—these were frequently taken by Robert M. Barr Photographers of Denmark Hill, who seemed to have the contract for several decades—it shows the male Sergeants assembled prior to their evangelical campaign, which usually lasted around ten days. It is very doubtful that the brass instruments would have combined with the concertinas to form a single musical ensemble. Rather, the brass would have been used to present instrumental solos or duets during the various meetings that the Sergeants would have held.

We may even doubt whether all nine of the concertinas ever played as a single group. There are two reasons for asserting this. First, it was not unusual, on occasions such as these, for the sergeants to present a somewhat inspirational picture that typified their evangelical zeal. Yes, they certainly possessed concertinas. Yes, they are likely to have had concertina lessons as part of their optional curriculum. But whether they could all yet play to a sufficient standard to form a coherent group is quite another matter.

A 1950s snapshot in my possession upholds this assumption. It shows nine Cadets with three concertinas, two accordions, a guitar, banjo, and flute; the flute, however, was the only instrument ever seen out on Campaign. Other records from the 1930s confirm this. A formal photograph of twelve Cadets actually on Campaign at Bletchley in 1931 shows two concertinas, which would have been used to accompany singing, to attract a crowd, and even to ‘drown out’ unwanted disturbances (see Figure 2). Another photo from that year shows a Brigade of eighteen at the Training College with but one concertina and a guitar, whilst a group photo from 1932 shows ten Cadets, but only the Officer with a concertina in hand.

Fig. 2. Party of Officer Cadets on evangelical campaign in Bletchley,

Buckinghamshire, 1931. The author’s mother is seated front left

(photo in author’s collection).

(Click to enlarge)

When comparing these photographs with the group of Sergeants in the ‘Picture Gallery’, then, it is necessary to bear in mind that the Sergeants were selected for their all-round proficiency, so that we might expect to see a higher proportion of concertina players amongst their number, but not necessarily to the extent suggested by their photograph.

NOTES

1. The feature was entitled ‘Two Salvation Army Bands’, 65-68.![]()

2. Butterworth’s patent is available online at www.concertina.com/craneduet/Butterworth-Patent.pdf. For a brief discussion, see Phil Inglis, ‘The History of the Duet Concertina’, Pt.3, Concertina Magazine (1985), 11-12, who notes that although the Crabb family claims to have invented the system in the 1880s, they neither patented nor made any such instruments at that time; Inglis’s article is available online at www.concertina.com/docs/Inglis-History-of-the-Duet-Concertina.pdf.![]()

3. See, for example, William Strang’s 1889 painting of a Salvation Army march (through typical London East End, Docklands surroundings) headed by concertina and tambourine; and E. Borough Johnson’s 1891 engraving of a Salvation Army prayer meeting, the leaders of which have a concertina and violin. Painting and engraving are reproduced in Cyril Barnes, God’s Army (Oxford: Lion Publishing, 1978), 27 and 31, respectively.![]()

4. The advertisement appeared in The Musical Salvationist, 18/Pt. 12 (June 1904), outside rear cover; published for the The Salvation Army Page 32, Pica 3 2006 Publishing Department by W.L. Simpson, London. On the various editions of the tutor, see Randall C. Merris, ‘Instruction Manuals for the English, Anglo, and Duet Concertina: An Annotated Bibliography’, The Free-Reed Journal, 4 (2000), 98, 105; also online at www.concertina.com/merris.![]()

5. Bramwell Thornett, ‘Why I Play the Concertina’, The Musician (2 March 1985), 136.![]()

6. Brigadier Archie Burgess was an accomplished player, and often provided a concertina solo item on the programmes of the Army’s International Staff Band. Though rare, his recordings on the Regal Zonophone label are still to be found in some private collections.![]()

7. Thornett, ‘Why I Play the Concertina’, 136.![]()

8. Ernest Ripley, ‘Fourteen Pounds Fifteen Well Spent!’, The Salvationist (10 June 4000), 24.![]()

9. Arthur Bristow, The Salvation Army Tutor for the Triumph Concertina, new and rev. ed. S.A., 102 (London: Salvation Army Publishing and Supplies, 1935), and The Salvation Army Tutor for the English Concertina, new and rev. ed., S.A. 103 (London, Salvation Army Publishing and Supplies, 1935). On the tutors, see Merris, ‘Instruction Manuals’, 98, 117.![]()

10. Norman Armistead, ‘Symbol of an Authentic Army Spirit”, The Salvationist (21 January 1989), 3![]()

11. Kurt Braun notes that Harry Crabb’s Crane system was designed so that the left- hand side extended to F (below the bass clef) and had a key to sound the low C (two octaves below middle c’); see www.scraggy.net/tina.![]()

12. Frank Butler, The Concertina (New York, Oak Publishing, 1976), 4![]()

13. Neil Wayne ‘Wheatstone’s 12-sided Duet: A Report on its Origin, Condition and Provenance’, online at www.free-reed.co.uk; for a far more detailed discussion of this instrument, see Neil Wayne, Margaret Birley, and Robert Gaskins, ‘A Wheatstone Twelve-Sided “Edeophone” Concertina with Pre-MacCann Chromatic Duet Fingering’, The Free-Reed Journal, 3 (1999), 3-16; also online at www.concertina. com/wheatstone-edeophone.![]()

14. Nigel Pickles, liner notes to recording The Mexborough English Concertina Prize Band, Plant Life Records PLR 055 (1983), 3.![]()

15. See the centrefold illustration in Concertina & Squeezebox, 23 (Summer 1990).![]()

16. The photo is online at www.harbour.demon.co.uk/tina.faq.![]()

17. Situated on Denmark Hill, South London, and overlooking Kings College Hospital.![]()